“I think our purpose here is to improve stewardship of the Earth, with compassion and respect for all life, to live with a sense of humor and adventure as we move towards spiritual fulfillment.” — Larry Stevens, senior ecologist for Wild Arizona and the Grand Canyon Wildlands Council

“Tell me about it!” Robin said after we hugged, heaved my luggage in the back, and climbed into the car. She’d picked me up at the airport after I flew back from a trip consisting of many firsts.

I thought, but where to begin?

With spending 13 nights outdoors, sleeping on the ground atop a sleeping bag, thin foam mattress, and tarp to keep the red ants and scorpions at bay, and hoping a rattlesnake didn’t slither onto the assembly in the night, nor a bat swoop down for a nip?

With the blazing temperatures — reaching 114 degrees in the height of the day — that got marginally comfortable only long after the moon rose? And slaking thirst with water that, at best, is luke warm?

With daily pooping into one of two communal metal boxes known as “groovers”, hidden discreetly in the shubbery away from camp? And, in the night, peeing into a quart-sized plastic cup to be emptied and rinsed out with river water in the morning?

With bathing in river water, wrapping yourself in a thin cloth sheet, clomping through the sand and rocks to your camping spot, quickly donning something to cover your tush, slathering moisturizing lotion over your body, then being whipped with wind-driven sand until your body feels like a sugar doughnut?

Sounds horrible, right? To the contrary, I took what was among the most exhilarating and inspiring trips of my life. Physically demanding, at times exhausting, it was a total blast. Specifically, rafting 226 miles of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, starting 15 miles below the Glen Canyon Dam, at a spot called Lee’s Ferry and designated Mile 0. Fourteen days later, the trip concluded at a spot called Diamond Creek, in the Hualapai Tribe Reservation. In between? Some of the most magnificent scenery on earth, taken in with physical adventure in the company of agreeable people.

More than a float down a river, it was a transformative journey through honest-to-goodness wild land, something I realized I’d never really done. All of the camping and hiking I’d ever done heretofore, mostly occurred barely out of earshot of a highway or railroad track. This time, two weeks without sight of so much as a telephone pole. Where I live, deer intrude on civilization. Down there, we were visitors to the deer grounds, and those of the big horned sheep, mountain lions, and birds of prey.

A Flagstaff, Arizona company called Arizona Raft Adventures provides pretty much everything in terms of equipment, food, and expert guides. The Grand Canyon — among God’s great terrestrial gestures — provides scenery unsurpassed anywhere in its grandeur. Its never-ending and mysterious rock formations seemed to have been fashioned by an ancient civilization. The Colorado River provides the water to cool you off in the heat, the thrill of rapid after rapid, the serenity of the flat water in between, where you might see the nose, eyes and ears of a beaver purposefully paddling by; or a duck shooing along a dozen tiny ducklings. The scrub shrubbery along much of the river produce scenes of bighorn sheep chewing on grass or, if you’re lucky, butting heads. The sky provided, on this trip at least, an unblinking sun by day, a spectacular galaxy of stars and satellites at night, far from urban light pollution.

My friend and neighbor, Mitchell, who is an accomplished hiker and camper, and who has a particular interest and experience in the Grand Canyon, asked me if I’d join him on this trip. We were supposed to go in 2021, but the lingering pandemic pushed into this year. His brother-in-law Mitch and Mitch’s friend Scott rounded out the D.C. area contingent on this particular trip.

I’m no tenderfoot, but it’s been quite a few years since I’ve slept outdoors. The last time was maybe 25 years ago when my son and I went on a couple of one- or two-night canoe camping trips on mild Virginia rivers. So I was frankly nervous about the idea of being outdoors for 14 consecutive days. In the Grand Canyon, you can’t run to Walmart if you forget something. In fact, unless you are injured or fall sick, once you leave the shore of the put-in, you’re committed for the entirety of the trip.

I’ll add a day-by-day summary at the end, but basically the trip starts the night before, at the Little America Hotel in Flagstaff. As if to purposefully contrast with the ensuing two weeks, the spotless, low-rise hotel’s rooms are sumptuously furnished, with sofas, marble showers, and the latest in comfy bedding.

After an hour-long orientation in a conference room by an AzRA staff member, each traveler is given two dry bags for the trip. Back in your room, you transfer your trip clothes and other items to the dry bags, and the next morning leave remaining luggage for storage at the hotel. A white AzRA school bus driven by an energetic staff member pulls up. Dry bags are stowed in the back of the bus, and everyone troops aboard for a two hour ride to Lee’s Ferry, about 15 miles south of the Glen Canyon Dam.

When we arrive at Lee’s Ferry, it’s hot and already the vestiges of civilization are behind us. The landing is little more than a parking lot and a shed. After a thorough briefing by Michele, our trip leader, time comes to get on with it. Forming gang-lines, everyone helps shift the bags to the boats. The guides tie everything down. You pick a boat, scramble in — now your feet are wet — and shove off into one of the world’s great rivers. The water is greenish blue and clear.

Having started close to mid-day, we only travel 12 miles the first day, but get to experience some exciting rapids and feel the sometimes vigorous splash of the waves. Our first camp site lies on the South side of the river, just below the Soap Creek Rapid.

Here’s a feature-by-feature description of the trip.

The groover: The universal worry people bring to these trips is, where and how will I, you know, poop? So I’ll start here. Guides set up two of these oblong metal boxes at each camp. Basically after you do your business, and use toilet paper sparingly, you sprinkle some sort of chlorine down in there and put the lid back. There’s a system for the groover, no less than for every other aspect of the trip. At the start of a path into a hidden spot thicket, the guides set up a handwash station. There’s a small canister containing the toilet paper. You take the canister with you down the path to where the groover has been discreetly hidden. And bring the canister back to the handwashing station when you’re done. Thus the canister, adorned in colorful tape, serves as a signal for whether a groover is in use. Having a shortly-after-breakfast regularity, I don’t try the groover until the next morning. I have what was for me, someone who assiduously avoids public restrooms for #2, a success.

The routine: Days follow a routine, but are never the same. The camp awakes naturally at about 5 a.m., as the sky starts to lighten. One or two of the guides arise early — they each sleep on one of the six boats — to make a big pail of hot coffee and prepare breakfast. I make two trips to the river each morning. One to empty and rinse my pee cup (and pee directly in the river) and a return visit to brush my teeth. I spit in the river, but rinse my mouth and toothbrush from one of my Nalgene bottles. I try to pack up my sleep kit before breakfast. Breakfast is social, with people sitting around on blue camping chairs. After busing my dishes, I hit the groover, then repack my dry bags in preparation for the day’s rafting.

Mornings the air isn’t yet hot; much of the canyon is still shaded. We might move along until lunch time. Often we stop for a mid-morning hike to see some natural or ancient Native American-made feature. Other times the hike and lunch stop coincide. Afternoons, high heat is often accompanied by sharp wind blowing from downstream, making hard work for the guides. By 4 or 4:30, we glide into a camp site. Passengers help secure the boats, then hop onto the camp site to find a spot. Some like to sleep down by the river, others on rock ledges above, at the base of a cliff. I go for shrubbed alcoves for privacy, hopefully with a flat rock nearby to serve as a table for my dry bags.

The pull-in to camp at first is my low point of the day. It’s when my regular-travel brain says: Go to the room, take a quick nap, shower, then head for the bar. Not out here. Still, after a few days in I find a comfortable pattern of site-finding, stuff-arranging, river-bathing, then socializing before dinner. A few evenings I’m content to sit by myself before dinner, sipping from one of the flasks of whiskey I brought, just to contemplate precisely where I am.

After claiming a sleeping spot, it’s time to help the guides unload everything needed for camp — food, kitchen equipment, everyone’s bags, handwashing stations, groovers, burlap bags full of adult beverages, water purification system, camping mattresses, tents (which only one or two people used once or twice), bags of folding chairs, ammo cans of miscellaneous items. Literally a couple of tons of materiel. While the guides prepare dinner, we’ve got 90 minutes or two hours to bathe in the river and socialize over beer or, in my case, whiskey.

It’s maybe 7 p.m. until one of the guides calls dinner time. We line up to wash hands and make way along the tall buffet table, eat, bus dishes, then wait for the dessert call. After dessert it’s dark and everyone rushes to get their camp site ready. By 9, it’s nearly dark and the camp falls silent.

The food: No one can quite figure out how, but AzRA and guides are able to provide fresh and amazingly good meals right up to the last day. Each oar boat houses an ice chest. There’s neither electrical refrigeration nor any opportunity to restock along the way. Dinners include steaks on the grill (twice), spaghetti with tomato and sausage sauce, chicken and bean stew, hamburgers and brauts, and barbecue chicken and pork, among other entrees. Always with fresh salad and a side dish. Breakfasts include blueberry pancakes, French toast, eggs made to order, and casseroles of eggs and green chilies. Plus bacon, Canadian bacon, or sausages. Lunches include chicken or turkey sandwiches, or tortillas filled with chicken or tuna salad. Bread always seems fresh. Peanut butter and jelly are available. Cookies, nuts, condiments of every description. Desserts are frequently cakes of varying flavors, baked in a cast iron dutch oven over charcoal.

The trip is no cruise ship, but neither is it hot dogs and beans. On the first half of the trip, Kat, AzRA’s food buyer (and excellent ukulele and guitar player and singer) is among the passengers. She wants to see how the food is actually consumed.

The guides: I’m continually impressed by their enthusiasm, stamina and skill. Your life on the river is basically in the guides’ hands. The river is the river, the canyon the canyon. Both are eternal, indifferent to whether you survive. Thus the guides are the important variable in the voyage. Our trip consisted of six boats, each with a guide. Four regular oar rafts, a raft designed for three people to paddle on each side, and a roughly symmetrical, pointed aluminum boat called a dory. An assistant guide, Laura, is the fiance of the dory guide Matt.

The guides not only oar all day, they possess surprising knowledge of the grand canyon itself, its history of exploration, the details of its various rock layers. I couldn’t remember the names of the layers, but now understand how plastic a substance rock actually is, over eons anyway. Guides work tirelessly, literally from dawn to dusk, directing the daily loading and unloading of the boats, ensuring everything is strapped down before morning departure. They set up and take down the kitchen, beverage and dishwashing stations, groovers. They take turns preparing meals, working in pairs. They make sure there’s plenty of purified river water. They’re quietly firm on what passengers are expected to help with, and what they, the guides, alone must do.

Most of all they possess gifted human relations skills. Never are passengers made to feel like city rubes, or people to be tolerated while the guides pursue their river passion. To the contrary, the guides genuinely and continuously engage with us, eager to share their knowledge of geology, wildlife, and of course, the subtleties of the river’s pulsing patterns of currents, eddies, whirlpools, waves and tongues.

Two of the guides are men my age, men of surprising durability and skill. Larry is a renowned kayaker. He’s run the Colorado River in one type of boat or another scores, perhaps hundreds of times. With a wry sense of humor and unflappable demeanor, he is asked by one passenger how he’ll handle a particularly tricky upcoming rapid.

“I’ll probably just back into it, close my eyes, and see what happens,” he replies.

Bob, a home builder from Colorado, is heavier and more taciturn, but warms up a lot as the trip proceeds. The first evening on the river he has the passengers saucer-eyed with what turn out to be completely tongue-in-cheek instructions for how to use the groover, using a single sheet of toilet paper. One evening he has everyone gather ’round, ostensibly to make duck callers out of the little flat plastic doodads that close bread bags. When we’re all about to test our earnestly-crafted duck callers, he tosses his and yells, “Hey ducks!”

Matt is the young male guide. He looks too skinny to row the dory day after day, but he does. On several occasions he calmly guides me around climbing situations when I’m gripped by my fear of heights, when I have to creep along a narrow ledge while finding handgrips in the rocks at eye level. He’s soon to embark on his first trip as trip leader. He’ll excel.

Riah, one of the three women guides, cheerfully adjudicates the demand for trips in her paddle boat, which gives a more involved, but less chill, experience than the other boats. She orders everyone when to paddle, and which direction, and when to stop. Passionate about geology, she talks in great detail about the canyon formations as we guide past. Comes a rapid, and she’s all business, expertly steering the boat through the thrills, then having everyone tap their paddle blades together in the air as a self-toast to a successful navigation.

Riah also nearly saves my trip. Early on I realize my made-in-China Teva boat sandals are coming apart. That would be a serious bummer. But Riah produces a gadget called a Speedy Stitcher, a sort of threaded awl. She wondrously sews them together with heavy thread. By golly they hold up until the very end. I’m tempted to trash them back at the hotel, but I bring them home so my wife can see the stitching.

Taylor, who goes by Tay-Tay, is a vivacious and funny red head, a seeker of knowledge and insight. We had a couple of deep discussions on the flat waters. With the arrival of a rapid, she becomes a river tigress, entirely focused on achieving the correct line through. In the bounding, splashing, noisy rapids, she lets out shrieks of joy, congratulating herself on a perfect run. We whoop it up along with her. It was with Tay-Tay that I go through the biggest rapid of the trip, known as Lava Falls.

One day the group hikes to a sort of grotto or deep, narrow channel in the rock, where we find smooth rock surfaces for a nap in the shade, our flotation devices serving as pillows. Taylor brings her guitar, and sings a set of songs that echo through the grotto. It makes for a weird sensation in my half-awake state, lying on rocks in this nearly unearthly setting.

Laura is our assistant guide. Although engaged to Matt, she participates on many of the boats, not always riding in the dory. She’s also quite capable of oaring. We end up on several river segments together, and I learn she is a student of human development in her work training people to become ski instructors.

Our trip leader is Michele, a relentlessly sunny woman with a brilliant smile. She’s rafted the Colorado through the Grand Canyon 60 times. Riding in her boat a couple of times I sensed I was in the company of pure competence. Ultimately in charge of safety and the trip’s general success, she governs with the lightest touch. In reality everyone wants to cooperate anyhow, and I don’t ever detect any sort of conflict. Before the initial put-in at Lee’s Ferry, she outlines what to expect. Each morning she lays a map on the ground as we gather ’round. With a stick, she retraces the prior day’s progress and points out what’s to come this day.

The river: The subject of a library’s worth of literature unto itself, the Colorado River between the two major dams — Glen Canyon and Hoover — is a living thing, albeit much different than it was before the damming booms of the 1930s and 1950s. Because of the Western drought, no flooding has occurred recently, so the water is green-blue and clear. It twists and turns, long stretches of placid flat water punctuated by rapids their inferior cousins, riffles, 118 in all. When last I visited, during a hike in the Canyon several years ago, the water was so cold I could barely go in for more then a few seconds, and then only to my ankles. On this trip, weather, drought and Lake Powell water release patterns have rendered the river much warmer. I’m able to take a daily bath, and wash out clothes. At one camp site, there’s a wonderful area where the water is gently flowing, at the mouth of an adjacent dry stream bed. I’m able to sit in the river up to my neck, a bum cheek on each of two stones, and let the cool water drive the day’s heat out of my bones.

We stop at the confluence of the Little Colorado River, at about Mile 62, Navajo Nation territory. The Navajos hold the river and the confluence sacred. We hike up along the shallow river, the color of a swimming pool, and float feet-first down a ripple for a few hundred feet. The water is tantalizingly warm compared to the Colorado.

The wildlife: Throughout the trip we see, in no particular order: big horned sheep, deer, beaver, mouse, peregrine, rattlesnake, duck, blue heron, bald eagle, hawk, bat, snowy egret, turkey vulture, osprey, raven, lizard, toads, cormorant, red ants, and tiny scorpions. At least that’s what I can name. We see many other insects, but no mosquitos. Ravens are no fools. On several days after the camp is packed up and boats loaded, ravens arrive to feast on the dinner and breakfast morsels left over.

The Canyon: On my second trip to the Grand Canyon, I was no less impressed than on the first. No photograph does it justice. The last time consisted of a hike down, two nights at the fabled Phantom Ranch, a hike along the bottom on the middle day, and hiking back out the third day. Seen foot-by-foot in the slow motion of the rafts, I am doubly impressed by the splendor of what a billion years of geologic activity has wrought, My mind wanders towards seeing things in the formations — a temple 2,000 feet in the sky, an array of singing monsters (Riah pointed out that one), rows of stern soldiers, faces of every sort. Maps, machines, animals. The rock seems almost alive, but with a heartbeat measured in eons.

The trip felt like a fantastical mixture of pleasant hardship — peeing into a cup by moonlight while admiring the surrounding Canyon vistas in the 2 a.m. chiaroscuro — and continual awe at the wild, rugged, stunningly beautiful totality of the Canyon. Was it luck, I wonder, that the guests were all so agreeable, or do like-minded people self-select to embark on this type of experience? No one spends hours pecking at their device.

You make fast friends, isolated in such surroundings with no email, phone service, or internet. Barbara, an athletic hairdresser from Wisconsin, transformed my ponytail into a French braid. A 70-ish but lithe Cass from Tuscon describes her late husband’s sailing from from Honolulu to San Diego. Near the end, after another trip passing by handed our trip a bag of ice cubes, Barbara’s husband Brett and I share the last of my bottle of Bourbon over ice, sharing the same coffee container. An athletic 30-year-old woman, Carissa, on the trip with her brother and their plucky mom, repeatedly offers me a hand when scrambling over the rocky hikes. I realize that at 67, I’m not quite as lithe as I was a decade ago!

People cheer one another on. At one location, we park the boats and climb onto a flat-topped rock with a straight drop to the river, which is about 60 feet deep. It’s a popular place for jumping. It’s no higher than a poolside high dive, but to me it felt like jumping off the Empire State Building. I’m the last to go, standing stupidly on the edge, gulping. Guides Riah and Laura and passenger Robert from Alaska are urging me on with mental tricks. Bob offers to hold my hand and jump with me. Everyone else is arrayed on the rocky beach below, waiting, urging. They start singing songs to get me to jump. Taylor tells Scott, “I’ve never wanted someone to jump so badly.” Finally, having no other honorable choice, I step off, yell “F—–k!” on the way down, and hear yells and applause when I bob to the surface.

Two weeks in, the trip ends, and a few hours later we’re back at the hotel. The river and canyon might be far behind, but they’ve — and the people I encountered — have made such an impression that they will remain in my heart.

See below: A detailed day-by-day account

Here’s the day-by-day detail, filed here mainly for my own recall:

DAY BY DAY

Day 1, June 4th: Waking up early, I make final arrangements of my gear and stow left-behind stuff, including my phone, in the suitcase to be stored for the trip duration. I make a final call to Robin first, though. It’s the last time I’ll be able to speak to her for two weeks. I grab breakfast and coffee at the 24-hour convenience store near the hotel. I’ve got butterflies over the whole affair. A group gathers outside in front of the hotel, chatting, making introductions.

Soon the white Azra school bus shows up. Next comes semi-pandemonium of lugging gear bags to the rear of the bus, loading, claiming seats. Eventually we depart for the two-hour ride to the launch site. Shortly out of Flagstaff, the passing scene turns to desert. A few miles before the final road down to the Colorado River the bus drops us off at one of two side-by-side Navajo Bridges. One is for pedestrians. The walk over produces amazing views. We watch condors loll around on the trusses of the adjacent bridge, which the bus has just crossed to pick us up at the other end.

Soon we’re down by the river, the rafts awaiting. Before embarking, though, we get a thorough pre-briefing by our chief guide, Michele. Everyone is issued a life jacket for the trip, and a dry bag containing a sleeping bag, tarp, and mattress cover. We’d loaded our two other dry bags the night before. The trip would prove so hot, I would end up using the mattress cover as a sort of sheet-thin sleeping bag. Each passenger chooses a boat/guide combo and climbs in. Off we go.

Slightly disoriented, I’m not yet fully in tune with the rugged beauty all around. The small vestige of civilization from which we’d embarked disappears behind us within a couple of minutes. Soon we’re under the Navajo bridges we’d earlier been walking across. We squint up at the tiny figures waving down at us.

Day 1 we’ve traveled exactly 12 miles, through the Badger Creek and Soap Creek rapids, before alighting at a camp site called Brown Inscription. Our first dinner – grilled salmon – is preceded by a humorous description of the groover and its operation by Guide Bob. Next, my first dunk-in-the-river bath, and first time set up a sleeping site. I figure out a way to keep glasses, pee cup, head-mount flashlight and other items within reach after darkness. Having completed the first evening routine, I realize there’s nothing to do but lay down on top of my sleeping bag. The air remains hot. I gaze up at a sky alive with stars and satellites. By and by, the moon comes up, bright as a down-facing searchlight.

Day 2, June 5th: First camp coffee – it’s darn good – dippered out of a huge pot. Having finished making the coffee, the designated guides are bustling about in the dawn, making our first breakfast. Notable: my first use of the groover, which is successful. Many firsts are thus overcome. After breakfast comes repacking stuff bags and helping haul stuff to the boats. We gather ‘round as Michele gives a short summary of where we’ve been and where we’ll be going that first full day on the river. She squats beside a spread-out map on the ground, using a stick to point out the features we’ll be visiting. Michele or one of the other guides will add an inspirational reading to the pre-departure ritual.

I end up in the back seat of Bob’s raft. I’m expecting a quiet, contemplative ride. Except, the trip is marked by the Sheer Wall, House Rock, North Canyon, 21 Mile, 23-Mile, 23½-Mile, Georgie, 24½-mile, Hansbrough, Cave Springs, Tiger Wash, and 29-Mile rapids. Lots of bumpy, thrilling splashing. The raft feels like a roller coaster cab. In between, the majesty of the canyon sinks in. We see it up close when, during a morning stop, the guides lead us on a steep, rocky hike to a high pool. Bob explains a lot about the rocks and formations. Our camp site is at the 30.5 mile side; we’ve covered more than 18 miles.

Day 3, June 6th: Having had another night of fitful sleeping, I join the paddle boat helmed by Riah, for a more physical day. I’m in the front left. In the front right is Kat, an Azra employee. She’s in charge of food purchasing and is on the first half of the trip to observe how the food is consumed. At breakfast she’d played a guitar and sang songs in the middle of camp for anyone who cared to listen. I’d sat nearby, and Kat and I discussed chords and keys.

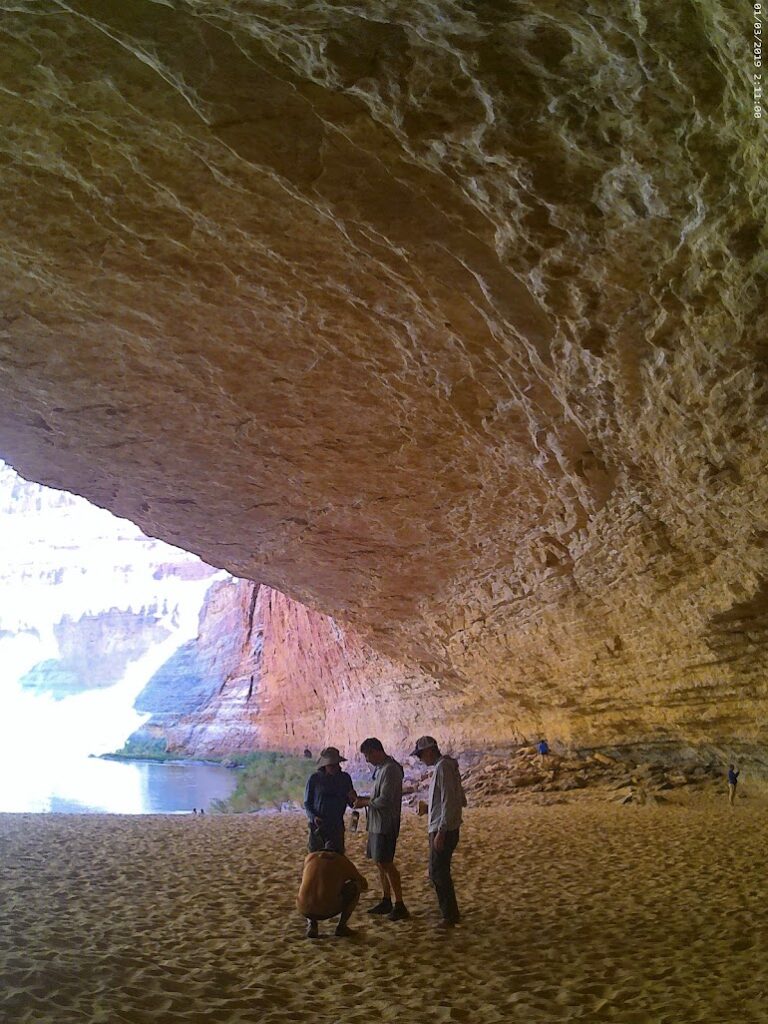

The day is cloudless and, at full temperature, way above 100. For the first time, I slide off the boat for a swim in the river. I need a tug from Riah to get back onto the paddle boat. We stop for a spell at an enormous cave, known as the Redwall Cavern. Its ceiling slopes back to the floor about 30 yards in, forming an eerie, reverse amphitheater. Another rafting group is also there. Everyone talks.

When my foot gets stuck in the mud at the edge of the river, I realize my Teva sandals are coming apart at the seams. This could be a real disaster, with 11 days to go. Later that evening, Riah – miraculously and generously – produces a gadget with which she sews them up.

We’ve paddled through the 36-Mile, President Harding and Nankoweap Rapids. After each rapid, the paddlers, at Riah’s prompt, raise our paddles and tap them together in a victory gesture. We pull in just below the Nankoweap Rapids for the third night’s camping. Before dinner I trade whiskey for beer with Brett and Barbara, an adventurous couple who are also dirt bikers back home. So far for dinners we’ve had salmon, spaghetti with meat sauce, and chicken tortillas.

Day 4, June 7th: Breakfast is French toast with Canadian bacon. I join Michele’s boat. She is encyclopedic in her knowledge of all things river and canyon. I learn she has a special stash of black licorice, just for people like me who love it. Michele reads daily passages from river- and nature-related literature. She tells me of her desire to become a children’s book narrator. She’s a remarkable leader.

We pull off for a hike of 616 vertical feet to see grain stores of ancient Indians. The air reaches 114 degrees Fahrenheit. Back on the river, I’m in the rear of the boat with Ryan, a heavily bearded, mild-mannered Millennial from Tuscon. Mid-day, we reach the confluence of where the Little Colorado River runs into the Colorado. The Little is said to be sacred to a local tribe. Boats parked, we hike a couple of hundred yards along a sidewalk-like strip of rock alongside the Little Colorado. Its water is clear and the ersatz turquoise of a swimming pool. This is good because often it’s brown and opaque. We wade into the shallow river and ride the current back to the confluence, and hike back to do it a couple more times. The water is blissfully warm compared to that of the Colorado. Other boat and hiking groups are in the area, and we exchange greetings. This day we run 22 miles of mostly flat river, but we do cross the Kwagunt and 60-Mile rapids, before camping at Carbon Creek just past the 65-mile mark. Dinner is grilled steaks (!) and mashed potatoes.

Day 5, June 8th: Breakfast is an artichoke-egg sort of stew on English muffins. I skip the hike that day, which takes place right after breakfast and before we get back on the river. I do some reading and catch up on my notes. I marvel at the wise and confident, camp-following ravens who strut around the deserted food area of the camp, pecking for the leftover scraps. Wandering back to the now cleared campsite, away from where the boats are tied up and the few non-hikers are hanging around, it feels as though I’m alone in the whole canyon. With my bottle of Campsuds, I use the opportunity to get a thorough bath for the first time, wading naked to my neck in the river and letting it flow around me.

Today I join the raft of Larry, a quietly funny man. He’s my age. We learn he operated a kayak river running company in South America. Approaching a scary rapid, another passenger asks how he plans to approach it. Larry deadpans, “I’ll just close my eyes, go in backwards, and see what happens.”

Today proves to be a day of many rapids, through which Larry expertly steers the raft so that I, in the front compartment, get soaked repeatedly. We pull off before one big rapid and hike up to an overlook so the guides can plan their strategies. The day’s rapids: Lava Canyon, Tanner, Basalt Canyon, Unkar, Escalante, Nevills, Hance, Sockdolager, Grapevine, Zorocaster, and 85-Mile. We camp between Mile 86 and Mile 87, another 20+ mile day.

Day 6, June 9th: Early wake-up. An eventful day because half the group will depart and hike out on the Bright Angel Trail. Today we’ll spend a good piece of the day in the only section of the canyon with any man-made infrastructure, where the trails from the South Rim come down in the vicinity of the famed Phantom Ranch. After breakfast we linger in camp, long enough that I have time to smoke a cigar. Then we do a short float to the Kaibab Bridge and park the boats at a boat beach.

Mitchell leads a small group of us on a 1.7-mile hike across the river on one bridge and back on another. We have time to loll around in the intense heat, crouching in a shady spot under some bushes near the beach. Then the guides return, and we have a short float to where the trail reaches the river. The new crew, having hiked down from the rim, is waiting, and we say good-bye to the departing passengers. We have lunch with the new people. I feel like a grizzled veteran after five nights on the river. I’ve been in the dory boat today, oared by Matt, who goes by his last name.

Short though our river distance is today, we traverse the Bright Angel, Pipe Springs, Horn Creek and Salt Creek rapids. Horn Creek is particularly violent; the dory feels like a bobbing cork. We stop early, having a long afternoon to regroup, repack bags, read, talk, and drink. The new and two-week rafters get acquainted. Nice group. Dinner is pork tacos. We camp at Monument Creek, just before Mile 94 and above the Granite rapid, which provides a steady white noise all night, and promises an exhilarating first few moments after the morning push-off.

Day 7, June 10th: Today I ride in the front section of Taylor’s raft, with friend Scott. Long day of rapid after rapid. In between Taylor, who goes by Tay Tay, and we discuss the Big Questions of life, philosophy. At her request, I explain the basic tenets of Judaism. We stop at the Shinumo Creek outlet to explore a side canyon and a hidden waterfall in a sort of grotto. The water feels great in the ongoing heat. In the afternoon as we approach camp, clouds gather. A few people set up tents just in case, but it never rains. We camp next to the outlet of Garnet Canyon at Mile 115, a 21-mile day. Rapids today: Granite, Hermit, Boucher, Crystal, Tuna Creek, Lower Tuna, 100-Mile (Nixon Rock), Agate, Sapphire, Turquoise, 104-Mile, Ruby, Serpentine, Bass, Shinumo, 110-Mile, Hakatai, Waltenberg, 112.5-Mile, and 113.5-Mile/Rancid Tuna.

Day 8, June 11th: A short mileage day, after a breakfast of pancakes and bacon. I return to Riah’s paddle boat. Another stop for a hidden waterfall. I’m surprised at the weight of down-dropping water. But it’s refreshing. We stop again at a deep, shady canyon called Blacktail. I’m tired and find a more-or-less smooth place on the rocks to take a nap, using the versatile life jacket as a pillow. Tay Tay is singing songs with a guitar nearby. The echoing voice and the heat put me in a surreal but pleasant light sleep. We spend 90 minutes there because of the heat and because, after more than a week of this, the guides sense we need an easier day.

We stop at Mile 126, having gone 11 miles. Dinner is burgers and hot dogs, along with the usual luke-warm beer, spirits, and water. The day’s rapids have been 119-Mile, Blacktail, 122-Mile, Forster, and Fossil.

Day 9, June 12th: I ride in the front of Michele’s boat. My opposite is Carrie, a lithe widow a couple of years older than me. She’s from Tuscon. We whoop it up in the day’s many rapids. A difficult hike at Deer Creek Falls. I say “difficult” because it challenges my fear of heights, The hike is offset by a cold, wonderful pool at the bottom of a 200-foot waterfall. This is the day we pass through the river’s narrowest section just below the 123-Mile rapid, where – inspired by Carissa – I plunge in, attempting to swim the 80 or so feet canyon wall to canyon wall. An astonishingly strong eddy current keeps me paddling in place until Michelle oars the raft over, asking, “Need a little help?” I grab the rope and she drags me through the eddy, whereupon I let go and swim to the opposite wall.

At one point Michele lets me try a stint at operating the oars, and I realize how heavy and difficult to maneuver these things are. Dinner is spaghetti and sausage. We camp just before Mile 145, having gone 19 miles. Rapids today were Nell’s Nemesis, Randy’s Rock, 127-Mile, 128-Mile, Specter, Bedrock, Deubendorff, Bonita Creek, Tapeats, 123-Mile, Helicopter Eddy, Doris, 139-mile, Fishtail, 140-Mile, and Kanab Creek. Bedrock Rapid is marked by a huge rock dividing the river left and right. Danger lurks for boats that mistakenly go left. Bob’s raft goes left, though, and while it doesn’t capsize, it gets stuck in a powerful eddy. Michele orders the other boats to tie up to the rock in case a rescue is needed. But Bob is a savvy old river runner. By force of will, he dislodges from the eddy and heads ‘round to the right, to our cheers. The sense of danger had been palpable. [Later in the summer, according to news reports, another company’s raft would overturn at that spot, after going left, and drowning a passenger.]

Day 10, June 13th: The trip feels long now. On the other hand, I am totally into the rhythms of off and on the boats, the unloading, setting up a sleep site and the rest of it. I do worry about Robin. In nearly 39 years of marriage, we’ve never been without communication with one another for more than a few hours. Now it has been a week and a half. Mitchell joked before the trip that I’d get used to bathing naked in a river with people nearby, and it’s true. The river gestalt of giving, as opposed to getting, privacy really works. Nobody looks at anyone else peeing or taking a bath.

Even the groover feels normal. In fact, the views from the groovers prove far superior to any other view from a toilet anywhere. Turns out the guides have brought six groovers, so as they fill after a few days there’s a fresh pair to deploy.

Today I ride in in the front of Larry’s raft with Mitchell, who has totally recovered from a short bout of dehydration. Today’s hike at the Matkatamiba Canyon was a super-challenge to my height aversion. Larry coaches me through some rough spots. Funny, a couple of years earlier I hiked all the way from the rim of the Canyon, to Phantom Ranch, and I felt like I could run a road race afterwards. Then hiked all the way back two days later. But crabbing on rock outcrops where you can plunge … that’s another matter.

The day is once again into triple-digit heat. We camp just before Mile 159, having traveled 15 miles. The camp site is a series of stepped, rock ledges fetching up to a sheer rock wall. It’s relatively free of the fine sand that characterizes most of the camp sites. It feels luxurious to pitch my sleeping bag against a steppe, the wall providing a place to set up stuff and lay out clothes to dry. I do some foot grooming. Dinner is a thick soup with chicken and beans. As darkness falls, I have a cigar with Robert from Alaska. Today’s rapids: 145.5-Mile, Matkatamiba, Upset, Sinyala, and Havasu.

Day 11, June 14th: Breakfast is a welcome bagels and lox with capers. Back in Tay Tay’s boat for a long day with lots of flat water and headwinds, but a couple of exciting rapids too. More great conversation under the sky, the canyon formations glowering down. We do a short hike at National Canyon, at a rapid with the same name. The big rapid that day is called Lava, and we stop before it and hike to a promontory so the guides can scope it out. We watch another expedition successfully navigate it. Tay Tay goes into game-face mode after we clamber back down to the boats and shove off. It proves to be an exciting ride, and everyone cheers when we’re through the rapid.

Nice but fully sandy camp site just below the Lower Lava rapid at Mile 180. We’ve gone 21 miles today, including long stretches of flat water with strong, hot headwinds. This late in the trip, relations with the other passengers has become strangely intimate. Barbara redoes my ponytail into a French braid. Dinner is barbeque sandwiches. The day’s rapids: 164-Mile, National, Fern Glen, Gateway, Lava Falls, Lower Rapid.

Day 12, June 15th: Lava, the trip’s biggest rapid, felt like a peak, and now, much as I love the pace of the voyage, I think about the upcoming evening, the last of the trip. The morning starts slowly. Two hikes: One is short and rocky to see pictographs by ancient Indians. Another involves climbing what is essentially a pile of rocks to a cave. Down by the boats, a passenger who has been ill for a couple of days is in visible distress. We give him and Michele space. She decides he must be evacuated. After satellite phone calls, we travel downstream to where the river contains a football field-sized, flat and rocky sort of beach. That will be the landing spot for the National Park Service helicopter. We tie up the rafts, and a bunch of us form a bucket brigade to wet down the area around the big, orange cloth “X” the guides have laid down. We repair to the boats, and soon the helicopter arrives, blowing up a short storm of sand anyway. The crew examines the passenger, who waves good-bye and climbs into the helicopter. The delay has taken about 90 minutes. I’m in the paddle boat today, and there’s a lot of paddling. The rapids are smaller and farther apart now, and the canyon seems to be getting lower as the miles pass. Mighty castles looming high in the air, their grandeur visible through the haze of great distance, have given way to lower, seemingly approachable cliffs. We camp at a wonderful, flat, spread-out campground at a spot called Ratashant Wash. A dry creek bed at the end of the site provides an easy entry into a gently flowing edge of the river. I wade in and sit on a pair of smooth rocks up to my neck for something like 15 minutes, gazing down river and up at the cliffs. Dinner is grilled steaks. Before dinner I give a short speech to thank the guides. We’re just above mile 199, a 19-mile day. The day’s rapids have been small and few – 185-mile, 187-mile, and Whitmore.

Day 13, June 16th : The last full day on the river. We stop in the morning to take a hike to a once-settled spot high above the river, where natives cut holes in the rocks to grind grain. We handle dessicated skulls of big-horn sheep and place them back on the ground where we found them, so subsequent hikers can wonder at them. Later we stop at a place called Pumpkin Springs. A rock that looks like a barn-sized pumpkin is topped by a pool of bluish and poisonous-looking water. But an adjacent flat cliff provides a perfect spot to climb to and jump into the river. Everyone who cares to, including the guides, hike up there and, with whoops, jump in. I get to the edge and freeze. In reality the jump is no higher than a standard high-dive at a local swimming pool. Looking across at the other canyon wall, it feels to me like jumping off the Empire State Building. My hesitation lasts until everyone has jumped a few times.

I’ve become a show. People on the rocks below and up on the ledge are all urging me to plunge. Bob the guide offers to hold my hand. Fat chance of that. Down below people start singing to me. Several times I march to the edge then stop. After maybe 20 minutes of this, I realize I could not face anyone if I climbed back down the back to the ledge.

Finally, yelling “fuuuuuuck!!!!!!!” I jump, and in about 1.5-seconds I’m in the water. Everyone cheers. A strenuous swim back to the rocks and, for a moment anyway, I’m the toast of the trip. Tay-Tay tells me she’d never wanted anyone to jump more. Inwardly I’m both relieved and sheepish, but height fear is not rational. It lives in the limbic brain. Anyway, my having jumped makes for a pleasanter afternoon.

After setting up camp just below Three Springs Rapid at Mile 216, I join a small group led by Guide Finger to the top of the rapid, where we wade in and “swim” the rapid’s couple of hundred yards. Actually you go feet first and hope you don’t drown. You try to breathe at the bottom of the swells. It’s exciting, but once is enough. For the last night outside, a sharp, hot wind like a blast furnace is coming up from downstream. We’d floated 17 miles, through the 205-Mile, 209-Mile, 212-Mile “Little Bastard” and Three Springs Rapids.

Day 14, June 17th: The last morning. I’m in Larry’s raft for the last day on the river, which will consist of only ten miles. For most of the miles, a tall formation known as Diamond Peak is visible downriver. It rises out of what will be our landing spot, just above the Diamond Creek Rapid. It’s a long rapid, but we won’t cross it this trip. The mood is philosophical, at least among the passengers. Many of the guides will spend a couple of nights in Flagstaff, then do it all over again with a new group.

When we approach Diamond Creek at Mile 226, the AzRA truck and school bus come into view, the first vehicles we’ve seen in two weeks, save a couple of helicopters. We pull in, and it’s all business. Passengers help the guides totally empty and disassemble the rafts, even deflating them there on the beach. An amiable driver/logistician directs where to load everything on the flatbed with its high racks on either side. Flo, one of the AzRA executives who will drive the school bus and us back to civilization, has brought cold soft drinks and ice. There’s a shelter with picnic tables and bag lunches. We dump the contents of our dry bags into big trash bags and return the dry bags to AzRA. I donate my crappy Chinese-made hiking hat that never stayed on my head in the slightest breeze.

After a couple of hours of exertion, we board the bus. What ensues: An hour ride – maybe it was 90 minutes – up and out of the canyon on a road made of rocks. Not gravel, rocks. The vibrating and bumping are severe and unending for the entire ride, literally the harshest vehicle ride I’ve ever had. I wonder why the rivets holding the bus together don’t pop out. Flo warned us the ride would be bumpy. The males acknowledge to one another that it’s necessary so sit in such a way as to keep one’s, er, sack from repeatedly whacking the seat.

Finally, we reach “sea level” at an impoverished Native American village by a main road. Yet across the street is a spiffy motel, where we stop for something refrigerated and a restroom that is neither groover nor river. Part of the way back to Flagstaff is on Old Route 66, and we stop at the famed Snow Cap in Seligman, Arizona. I have a large vanilla malted shake. An hour later we arrive back at the Little America hotel in Flagstaff. Happily, our left-behind suitcases are standing in the lobby with room keys attached – no need to wait in line! Once in my room, I dump my plastic bag on the floor. But before beginning the sorting and repacking for the next morning’s flight home, I dig into my suitcase, retrieve my phone, and call Robin. A moment later she knows I didn’t drown or get stung by scorpions, and I know everyone in the family is still alive and that the house hasn’t burned down.

At once relieved, joyful and let down, I proceed to take the greatest shower in history. The Little America has fantastic stall showers, big glass-enclosed chambers equipped with those rain-like showerheads. I leave conditioner in my hair for like 15 minutes. A couple of hours later, the entire trip, guides included, gathers in the hotel bar for food and drink, stories and good-byes. It’s fun to see people washed and dolled up. Later I fall into bed and sleep soundly. Next morning I meet Scott, and we Uber to a shuttle station to catch a van to the Phoenix airport for the flight home.