I once read a newspaper interview with a diet expert. He cautioned against ordering fattening things in restaurants with the intention of eating only half. That went for the bread and rolls, too.

“We’re finishers,” he said, referring to the human race. Meaning, it’s unnatural and therefore unsustainable to try and resist the remaining mound of buttery lobster mac ‘n’ cheese on your 15-inch plate.

“I’m a finisher,” I thought to myself. I like to take things to their proper conclusion.

But sometimes you can’t finish. Sometimes the food’s no good. But even when it’s just what you wanted.

The other day, a day off, I rode my motorcycle up to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Just to get some bracing, cold-air miles in before the winter fully sets in. I passed the solemn statues in the slanting sun. I love the fields and cemetery, but today I was mainly airing my Harley and loosening my skills.

Arriving in the quaint downtown in the early afternoon, I lucked into a big parking space right on the main drag. The meters sported signs that until New Year’s Day, daytime parking was free. Great! I walked two doors down to a restaurant specializing in burgers. It was called, Gettysburger.

The decadent burger was scrumptious. But the bun, burger and fixings combo was roughly the side of a softball. Delicious as it was, I simply couldn’t finish it.

Books too. I like — I determine — to finish a book, even if it turns out dull. Sometimes, though, the hill gets steeper the longer you slog. I have the Roy Jenkins biography of Winston Churchill. It was published in 2001 and I probably bought my copy around 2003. It’s become a joke between my wife and me. I’ve dragged that book on countless vacations and business trips and by this past October I was maybe, generously, halfway through. Every time I start a new book, Robin says, “But, hon, aren’t you going to finish ‘Churchill’ first?”

Now, I admire Roy Jenkins. He was a meticulous researcher with deep insight into British history and politics. He was a long-serving member of Parliament. He wrote 18 books. Yet while I love his ultra subtle senses of humor and irony, his subject-matter command, and his ability to craft 50-word sentences — I simply couldn’t finish the book. It was simply too dense, too detailed. I can take dense, I can take detailed, I can take 50-word sentences. But facing them in combination, I usually fall asleep.

By some benign gift of the universe, a brand new 2018 biography of Churchill arrived at the WTOP studios, sent on speculation by the publisher. This one is by Andrew Roberts, another great British historian. You can tell when an author is British. They only use a single ‘ mark to open and close quotes, not the American “. Unlike the late Jenkins, Roberts is younger than I am.

“Churchill” sat for two weeks in the newsroom. That’s it, I said to myself, I’m taking this one home since no one else seems to want it.

So, I found the point in Churchill’s life I’d reached in the Jenkins book, closed and shelved it, and picked up the story at the same point in the Roberts book. MP Churchill is out of a ministerial position in, and arguing with, the Stanley Baldwin government between the wars. For sure, Roberts writes like a Brit, but a more contemporary one. Plus the scholarship and document cache have grown in the 17 years since the Jenkins book, so Roberts has — if this is even possible — even richer material.

Strangely, it feels like I’m on a smooth continuance, not a graft of unlike species.

Having read — from beginning to end — multiple biographies of Lincoln, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Harry Truman, I’m well aware they’re anything but clones of one another. For instance, the Carl Sandberg’s one-volume version of Lincoln and that of the late David Herbert Donald published decades later show a vast difference in style, scholarship, approach, even possibly of purpose. Though both are magnificent.

The best books leave mental residue forever.

Whenever I hear of an American soldier’s death, say in Afghanistan or Yemen, I’m reminded of this passage from the poet Sandberg:

“In many a country cottage over the land, a tall old clock in a quiet corner told time in a tock-tock deliberation. Whether the orchard branches hung with pink-spray blossoms or icicles of sleet, whether the outside news was seedtime or harvest, rain or drouth, births or deaths, the swing of the pendulum was right and left and right and left in a tock-tock deliberation.

“The face and dial of the clock had known the eyes of a boy who listened to its tick-tock and learned to read its minute and hour hands. And the boy had seen years measured off by the swinging pendulum, had grown to man size, had gone away. And the people in the cottage knew that the clock would stand there and the boy would never again come into the room and look at the clock with the query, ‘What is the time?'”

“In a row of graves of the Unidentified the boy would sleep long in the dedicated and final resting place at Gettysburg. Why he had gone away any why he would never come back had roots in some mystery of flags and drums, of national fate in which individuals sink as in a deep sea, of men swallowed and vanished in a man-made storm of smoke and steel.”

How can you forget a passage like that? It’s one reason I’m fond of Gettysburg.

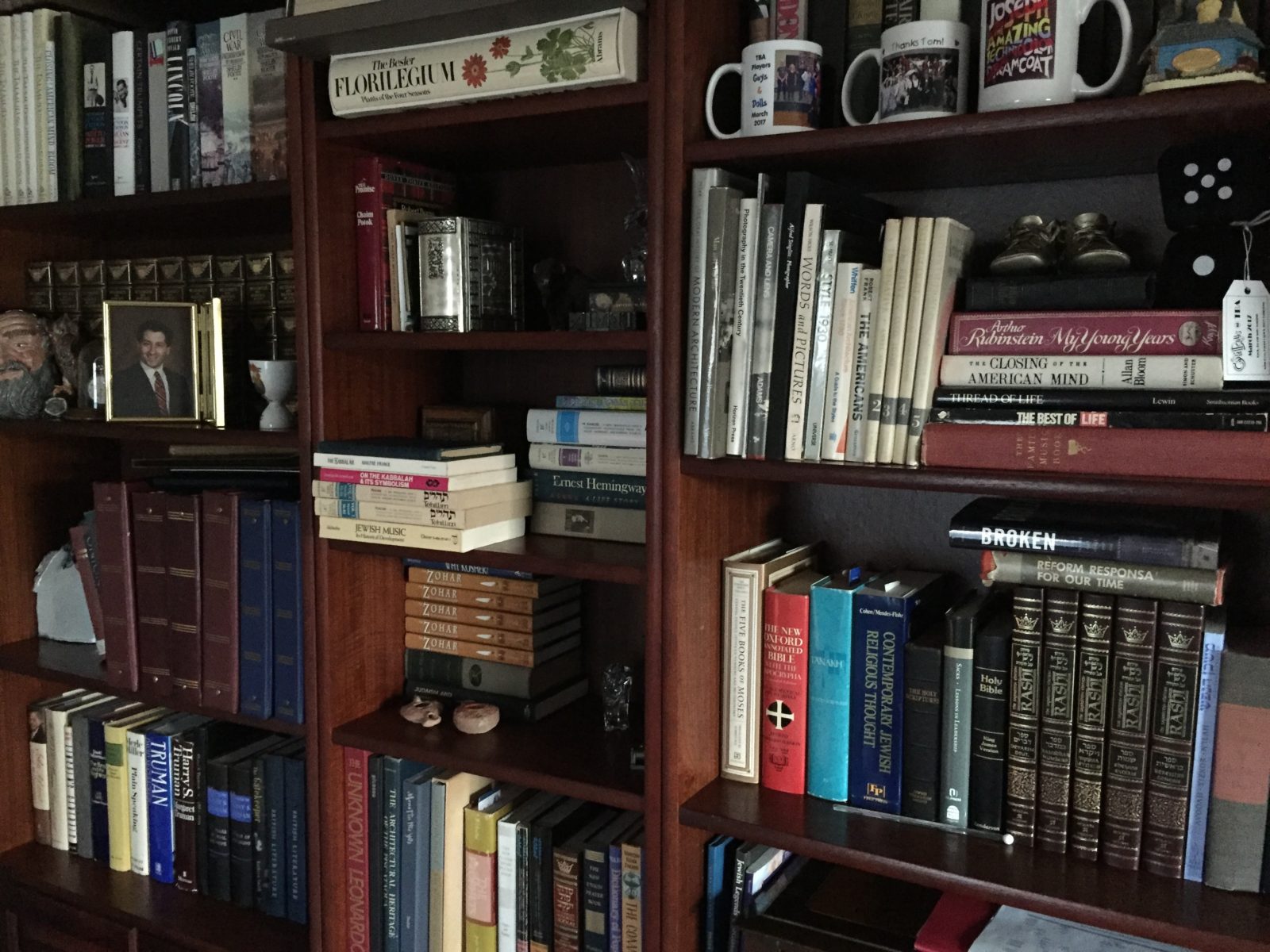

Even what you don’t finish can still leave value. I couldn’t get through more than about two and a half volumes of a masterful trilogy on the historicity of Jesus by the Catholic priest, original thinker, and Notre Dame professor emeritus John P. Meier. In checking my shelves for this post, I’ve learned there are two more volumes in the series! The last one came out in 2016. Now I’m really behind.

Like Jenkins and the others, Meier is capable of nearly unimaginably comprehensive research. Somehow he assimilates it all into cogent and readable books. In this case I felt I had enough understanding of the theme that I was content with the first two volumes, although I own the third.

But what I did read changed my understanding of history, theology, and the shibboleths of faiths. In some tangible ways Meier’s approach, though not his subject, affected how I study Torah, which I have regularly for 25 years. An unbeknownst gift from a Roman Catholic priest.

So my 2019 resolution is … I’m going to finish the books I start. Or perhaps not.