Travel to distant countries always brings joy. But certain places take hold in your heart. Israel did that a long time ago. Now Vietnam has done it. Our trip, in November of 2023, was conducted by Vermont Bicycle Tours.Â

I must start with our guides for the two weeks: Tranh Dihn Vo, who goes by Zin; and Kha Le, who goes by Kha. Zin is the older, more serious of the two. Kha is more voluble and jokey. They made a wonderful pair, and we liked them immediately. Moreover, they worked tirelessly to make every detail of the trip rewarding. No detail was too small. They directed us to laundry, custom-made clothing, how to find egg-coffee in the south. They added a sunrise walking tour of Hanoi, where we saw how the city wakes up.

Here are some of my impressions from the trip:

The Scooters:

I’d seen videos of them, but I’d never witnessed the scooter culture of Southeast Asia until now. It started the moment I left the airport in Hanoi. The airport is a good half hour or 40 minutes from the edge of the city. It was a cloudy, off-and-on rainy afternoon. Once the cab left the airport itself and entered the highway to Hanoi, the first scooter appeared. Within moments they seemed to be everywhere, driven by old and young, male and female, in sneakers, boots or flip-flops. An infinite variety of two-wheel shapes and sizes, none like the big, heavy motorcycles that are standard in the U.S.

But on that homely highway into Hanoi, the scooters were pretty much confined to their own lane. Once the cab reached the city and its instant density, the scooters coalesced into something else.

They formed giant, undulating, endless snake of narrow vehicles, at times oozing, at times flowing rapidly through the streets, dividing around cars, trucks and buses, which they outnumbered, it seemed, 1,000 to 1. Every human activity – taxiing, commuting, vacationing, taking the kids to school, honeymooning – these all take place on two wheels, in rain or shine, every day, and with less than 150 cc of internal combustion power.

Men and women on scooters deliver meat, fish, fruit, bricks, flowers, dry concrete, wholesale household goods, mail, live ducks and chickens, small primates, nursing infants, ladders, furniture, racks of clothing, rolls of textiles, propane tanks and gasoline cans …

Vietnamese convert scooters into pickup trucks, tractors and farm wagons. Scooters range from shiny new Hondas their owners wash and wax on city streets, to miserable, rusty, mud-caked jalopies of uncertain origin roaming the villages and rural roads, their tiny old engines emitting a puff of smoke every 4th stroke.

My first morning in Hanoi, still slightly disoriented from having departed without Robin and landing on an afternoon 12 time zones away, I ventured out on a self-guided walking tour of the city. Like every first timer, I faced the uncertain challenge of crossing the street in Vietnam. Traffic lights, crosswalk signals, rights of way – they’re all largely-ignored suggestions. I eventually had to cross several streets converging at a giant roundabout near the classical music hall. There, the mighty crush of cars, trucks and buses enveloped on all sides by the thick stream of scooters made crossing seem like a suicide run.

But the traffic only looks insane. In fact, it operates like a school of millions of minnows all swimming through confined sluiceways. They never stop moving and they never collide. Stepping off the curb, you must keep marching across the avenue. The vehicle ooze will simply divide around you and regroup beyond you. A bus might steam right up to your face – one of you stops and gives way. It’s not personal, more like playing a combination of rock-paper-scissors and chicken. Eventually you reach the other side. It helps to not lose heart and stop in the middle. Rather, you must keep up the mental calculation.

Never think the sidewalks provide solace from the scooters, oh no. The curbs in Vietnam cities are shaped to form ramps just perfect for scooters to scale the sidewalks. Each block has scores or hundreds of vehicles parked perpendicular to the street such that you’re lucky to have 12 inches of sidewalk. Shopkeepers ride their scooters right up into their shops.Â

On our first evening in Saigon, the guides arranged for us to take a city tour on Vespa scooters. On cue, a fleet of Vespas arrived on the sidewalk outside our hotel, The Majestic. Each of our group of 17 had a personal Vespa driver, and several other drivers came along as wingmen in the crowded din of traffic. We had a blast, and strangely I never felt fear as the Vespas navigated the hordes of vehicles, now swooping down an open patch of road, now squeezing between a car and a bus. We stopped for drinks on the rooftop bar of a skyscraper, and at a famous Bahn Mi shop. Plus, it was my first time on the back of a two-wheel motor vehicle. The last time was in college. The drivers were skillful and sure-footed. I marveled at the machine I was on. It was made back when Vespas had clutches and multiple gears, probably 40 years ago.

The Food:

Our food venues ranged from an elegant, catered dinner for the one-time home of Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge in Saigon, to a steaming tent, sitting on tiny plastic stools where we sweated through street food at the water festival in Siem Reip, Cambodia (an add-on trip we and a few others in our group took).Â

My first evening in Vietnam, I’d arrived in Vietnam ahead of Robin because of visa problems. I’d been traveling alone for what seemed like days, including a layover in Doha, Qatar so long I had time to take a tour of the city and eat in its open-air market. Subsequent Arrival in Hanoi, on a gray, drizzly afternoon, felt disorienting. After getting through the visitors and customs lines, obtaining Vietnamese currency, and climbing into a cab, I had a second wind observing the strange and sprawling city. After checking in to the Melia, though, I simply had to take a nap.

Awakening in the early evening, I went to the concierge, who directed me to a popular pho restaurant I could walk to. It was crowded but I soon learned you just sit where there’s a stool at any of the tables of 6 or 8. My tablemates were from all over the world, but a couple of them spoke English. The pho arrived within two minutes, and I dug in. Or, rather, slurped in.

The next morning, I set out on a walking self-tour of Hanoi. Rather than breakfast in the hotel, I found a place around the corner – the “place†being a tarped-over alley covered in worn green material like old Astroturf. For about $1, I had an egg sandwich with pickled vegetables and a glass of hot tea. Vietnamese men, mostly young, in suits, looking like junior bureaucrats or bank clerks, sat nearby on low chairs. We nodded pleasantries. The place would be shut down in 10 minutes in Montgomery County, Maryland, for sanitation and a thousand other code violations. But neither from here nor from any other food establishment in our three weeks of travel did I experience the slightest gastrointestinal problem. Sitting in this makeshift place on a busy side street felt like traveling, not touring.Â

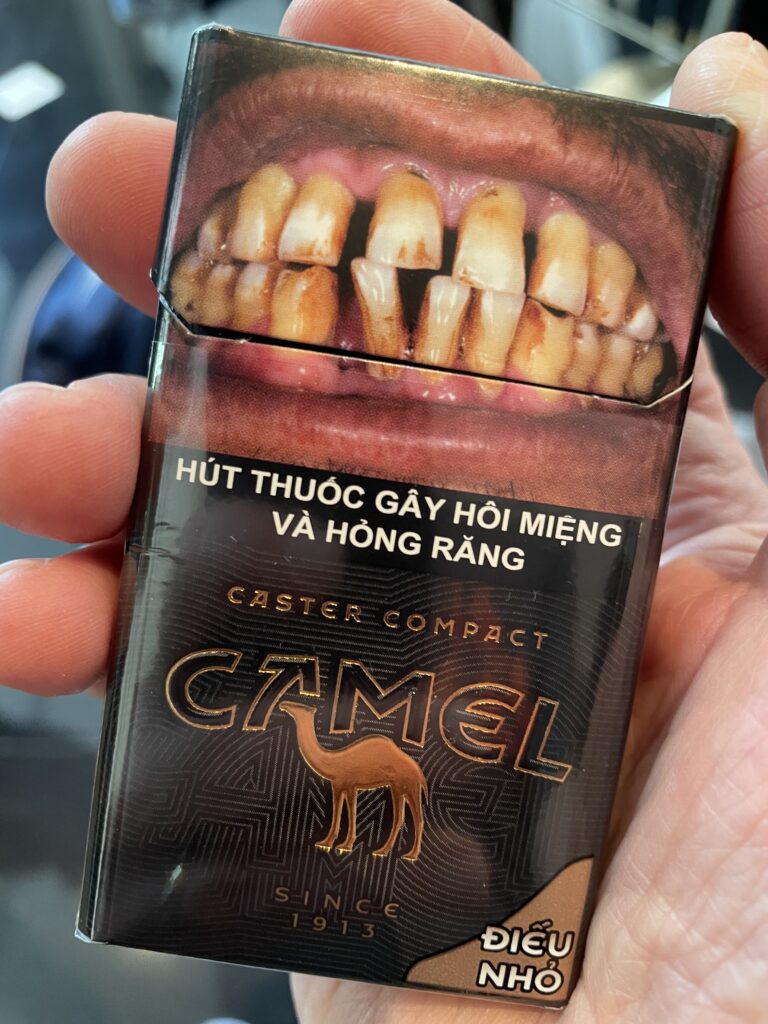

A bad habit admittedly, but when on foreign travel I sometimes take up cigarette smoking. Vietnam’s government unsuccessfully discourages smoking by requiring packages to have detailed warnings and lurid cancer photos. Yet a pack of 20 slender filters costs about 50 cents.

For lunch, I found an uncrowded, open front restaurant on Douong Thanh street, where the waiter set up a wok with cooking oil on a little Sterno stove. He placed on the table chunks of fish and a mess of greens for me to cook right there. Rice noodles, peanuts, raw bamboo shoots and fish sauce completed the delicious lunch.Â

At one dinner in the hotel in Hue one evening later in the trip, I had the craving for a pizza, so I ordered one, needing a break from the Vietnamese dinners.Â

Somehow, the street food often seemed the most adventurous. One night in Hoi An, Robin and I opted for an evening of “grazing†on street food. Bahn Mi sandwiches, sitting on the sidewalk on doll-sized stools; slices of taco-like pressed dough with vegetables and unidentified meat. Delicious!

We also liked the Cambodian street food, eaten at the Water Festival just a half mile or so walk from our hotel. This included all sorts of meats and meat shapes on sticks, plucked from displays under rags attached to spinning fans to keep the flies away. Also, fresh boiled corn-on-the-cob, even (for Robin) fried crickets scooped from huge woks full of them, and “fried†ice cream.

Throughout the tour we’d have lunches and dinners with large prawns still with their heads, fried tofu, fish, marinated pork and chicken, salads, and always pho broth and sticky white rice. VBT provided nice restaurants. Meals varied a great deal, but somehow came to taste repetitive. I liked the piquant items – the fish sauce; the pickled vegetables; the spicy, ketchup-like Chin Su. Also, the pungent, spicy Vietnamese coffee give a welcome kick each morning.

The Money:

In Vietnam, you feel like a billionaire. Maybe a trillionaire. That’s because $1 equals 24,000 Vietnamese dong. It takes getting used to. A 300,000-dong cab ride sounds expensive until you do the math.Â

Because of the miniscule value of a dong, you don’t find coins in Vietnam. The smallest paper bill carries 1,000 VND. We regularly had to withdraw millions of VND from ATMs and ended up with lots of 500,000 and 200,000 VND notes, each adorned with a smiling “uncle†Ho Chi Minh.Â

The Vietnamese mostly pay by pointing their smart phones at merchants’ QR codes.

ATMs, though, can be tricky. Wanting 10 million VND, we coaxed 8 million out of a machine in a hotel. It refused to give more. We tried several other ATMs within blocks. At the last machine, at 4:30 in the afternoon, a bank ATM would not return the card. The bank would close at 5 and tomorrow would be Saturday and the bank closed. Inside, the bank staff said they wouldn’t open the machine unless we had our passports, which were back at the hotel. I sat in the lobby, vowing not to leave until they retrieved the card.

Robin trotted back to our hotel. I sat in the lobby, threatening to call the police. At about 6 minutes before 5, Robin came roaring up to the door on a scooter, driven by a green-helmeted Grab driver. Passports produced, we got the card back. But I had no way to pay the driver. The scooter-hailing services don’t accept cash or credit cards. You must use their app. Rather than fuss with downloading an app and setting it up, I simply thrust 250,000 VND into the driver’s hand. He grinned and thanked me profusely. That $10 was probably three days’ worth of ride revenue, and it was all his. We saw him scoot by on a nearby block two days later. He gave us a big wave.

The Biking:

Our guides presented the VBT bikes, introduced to us at our hotel in Hoi An. We went there after leaving Hanoi, the trip having been rearranged because of rain. The rugged bikes of the hybrid style looked homely and well used. But they were in excellent mechanical condition. After adjustments and testing out in the parking lot, we ventured out for an afternoon ride. We crossed the highway in front of the hotel and pedaled shortly into more rural conditions. “Road†in Vietnam can mean anything from a four-lane divided highway to what in the U.S. would be considered a footpath or logging road.

We had our first views of what would be days of Vietnam scenery. Rice paddies, farms and village after village. The villages presented cinematic sequences of shanties, fine homes, shops and restaurants, animal pens, schools, garages and workshops – all crammed side by side, each village appearing as a self-sustaining ecosystem.Â

Dogs would laze in the lanes, mostly unperturbed by the bicycles, much less by the jumble of scooters, tractors, bicycles, cars and trucks. Chickens crossed our path, miraculously avoiding getting mangled in the spokes. Children would shout out to the obvious tourists. Hello! Hi! We also heard the occasional “Fuck you!†which brought laughs on our parts.

People going about thousands of activities also smiled and waved. I wondered what they thought. People aren’t naive; yet I wondered, what do we look like – people who flew 8,000 or 10,000 miles in great airships, to pedal through these villages? That man fussing over a battered, ancient scooter – had he ever traveled more than 100 miles from this village? The wrinkled ancient, sitting on an overturned bucket and pulling on a Thang Long: He must remember the American chapter of the Vietnam War. The woman washing dishes from plastic basins on the sidewalk: Does she imagine having a Bosch dishwasher and potent pellets of detergent?

The bicycle rides traversed flat country – except for one day. The guides gave us a choice that day when the destination was a town beyond Danang. The road there, Deo Hai Van, a mountain pass on National Route 1, rose for six miles uphill, reaching an elevation of 1,627 feet above the sea. We could choose to ride up the mountain (and back down the other side) or ride the van up and over, to bike at another destination, a flat route around a lagoon in the next province, Thua Thien Hue.Â

The fit, 30-something couple, one other tourist who is also fit but a decade younger than me, and I chose the hill route. The van dropped us off, along with guide Zin, and proceeded with everyone else headed to the lagoon. Zin would bring up the rear of the little party riding uphill. The other three were nearly out of sight before I clipped in. Sixty seconds into the ride i realized this was going to be a very steep, long climb. So steep, I opted not to stop at some of the magnificent views of Danang and the ocean from high above, worried whether I’d be able to get the bike going again!Â

Cars, buses, trucks, scooters and motorcycles passed, the trucks whining in low gear. One group of motorcyclists coming downhill laughed and shouted, as if they’d seen a fool foolishly trying to scale the mountain on a bicycle. Little Buddhist prayer spots and tiny coffee shops appeared in niches off the road. I kept saying to myself, you ran 13 marathons, you can do this. As the miles painfully passed quarter by quarter, I could see the road zigzagging back and forth in the distance, in faraway heights, magnifying how far I had to go. Worst were the switchback turns, where the angle of ascent grew the steepest.

At about the 4.75-mile mark, I realized I would make it after all. I’d been tempted to stop and just climb onto one of the three vans trailing. When I paused for a drink of water, Zin came up from behind, grateful that I’d stopped and he could catch up. He led the way, and we slowly cranked up the road, now reaching 8% and 9% grades, to the summit.Â

The others were waiting at a cafe, drinking coconut milk. Fellow biker Tim handed me his coconut and motioned for me to have a gulp. It had drizzled, and now it was cold at the top. Zin loaned me a neon yellow-green windbreaker for the ride down, another six or seven miles, where we’d meet the others at a restaurant.

In all, biking came with the qualities of a dude ranch. Three vans took 17 people plus two guides to the biking spots. Two other trucks ferried the bikes, and their drivers kept the water bottles filled, guided us through busy intersections, and performed any adjustments. While we sat on benches in rest stops at rustic restaurants, the drivers would arrange the bikes in a neat row, facing the street.

I didn’t experience a single dull minute while biking. Whether passing through a field of dragon fruit plants, a rice paddy crisscrossed with paths on which water buffalo wandered, a magnificent cemetery of mosaic tile monuments, or a noisy village, the encounters resembled nothing like we’d seen in the West.

A Few Vignettes:

So many sights and situations…

At the park commemorating the Cu Chi tunnels complex, Zin arranges a talk for us by former Viet Cong officer Huynh Van Chia, whom he referred to as “uncle,†a common Vietnamese honorific for referring to an older man. Zin translates, as Uncle, who is missing his right arm, describes life during the tunnel warfare. More than a half century after the end of the U.S. war in Vietnam, here I am taking a selfie with Uncle Huynh. Equally sobering are recreations of the booby traps set for American GIs to stumble into.Â

For our final evening together in Vietnam, the guides have arranged for a catered dinner at the house once owned by Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge. It is both a private home and an event venue dotted with historic items, and a gracious house. After dinner and toasts, I play “Over the Rainbow†on the grand piano, which is recent. The caterers try to limit us to two glasses of wine. The guides intercede and the wine continues to flow.

Our guides were great in a thousand ways. One day one of my bicycle shoes fell apart. Kha whisked them away, and the next morning returned them all re-glued so they would last the trip. I think the total was something like $2.

Oddly the Hanoi part of the tour did not include the Museum of Vietnam History I’d toured on that first day before Robin arrived. The museum is housed in the slightly dilapidated Indochina building of 1910. I wandered in during that somewhat surreal day alone in Hanoi. No one was at the ticket counter. From the far end of a corridor bisecting the building, a bored-looking young woman glanced up from her phone and motioned me in. “Just go,†she seemed to say. So I spent the next couple of hours wandering the rooms, having the place nearly to myself. Hardly examples of modern museum science, many of the displays were more makeshift than you’d find in the lobby of a U.S. high school. Still, I was transfixed by the long history of Vietnam, in which the United States’ involvement takes up a significant, if short, chapter.Â